|

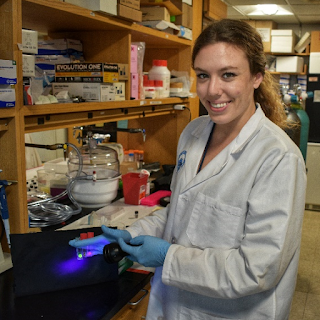

| 2018 Hillenkamp Fellow Haley Marks with the first prototypes of the oxygen-sensing hydrogels, developed in collaboration with BU |

"I actually found out that I won in December, just as I was getting ready to fly home for the holidays," she recalls. "I was packing when I got a call from Rox Anderson, the director of our center, the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, congratulating me, and I got all flustered. I swung by the lab on the way to the airport to celebrate the news with my mentor, Dr. Conor Evans, and our colleagues, and ended up missing my plane!"

The missed flight has been more than worth it for Marks, who has been at the Wellman Center since February 2017, working with Evans and his team on an oxygen-sensing bandage known as a SMART (sensing, monitoring, and release of therapeutics) bandage. "We've been working on the oxygen-sensing element from a chemistry standpoint," she explains. "This fellowship, which supports our interdisciplinary, translational work, has given us the opportunity to take new, creative approaches on the therapeutic aspect of the bandage." Previously, their oxygen sensing bandages had been created for intact skin - for conditions such as grafts, bacterial infections, chronic sun exposure, for example - utilizing different formulations of a paintable, or sprayable New Skin™-based liquid bandage: "We spent a lot of time in the arts and crafts store trying to adapt airbrushing techniques."

These days, the team is homing in on creating a bandage that doesn't just sense and monitor oxygen levels, it treats open wounds and burns as well. Upon receiving the fellowship, Marks and the Evans team established a new collaboration with Dr. Mark Grinstaff's lab at Boston University, a group with expertise in biocompatible hydrogels that specifically cater to weeping wounds. Together, the labs have already developed a number of oxygen-sensing hydrogel prototypes.

"The SPIE-Hillenkamp Fellowship means that I've been able to work on new, biocompatible materials that are open-wound friendly," says Marks. "You can place them over severe injuries like a gouge or laceration, for example, or use them in a situation where you have a wound that's oozing exudate. These new versions of the bandage are able to soak up the exudate the way a traditional bandage material would, while also releasing therapeutics to treat the wound, and providing oxygen-sensing feedback."

|

| Demonstration of the oxygen-sensing hydrogel's response to extreme changes in environment: left- in the absence of water and air the bandage red phosphorescence is dominant and is indicative of poor tissue health, right- when in the presence of normal levels of water and air green fluorescence is dominant |

Haley gives me a mini-demo of the latest iteration of the SMART bandage: the team's sensor dyes are embedded in robust biocompatible hydrogels that start out in liquidish form - "like jello! They have the exact, same consistency as jello!" They conform to the shape of the wound and then solidify into a wound dressing. Marks shows me how the bandage, exposed to oxygen-rich room air, glows green; another one that gets a humid, oxygen-deprived environment, under nitrogen gas, glows orange, the early warning sign; and one that's exposed to a dry, oxygen-deprived environment, again, under nitrogen gas glows red.

|

| The 'SMART' bandage can be imaged using a commercial DSLR camera with customized filters |

|

| The 'SMART' bandage phosphorescence emission is also visible by eye under UV light |

It's cool, colorful, and impressive. So where does the translational focus fit in? That's one of the most exciting parts, notes Marks. "As a part of this fellowship I not only have my scientific advisor, Dr. Evans, I also have a translational sciences mentor, Dr. Gabriela Apiou. With Dr. Apiou, I connect with our clinical collaborators to guide designs and implement changes to ensure that we always meet clinical needs and match clinical workflows. For example, when we're choosing what type of drug to load into the new bandages, we make sure to take into account important down-the-road decisions, such as ensuring that those drugs are manufactured in a facility that functions under GMP, good manufacturing process. It's all about making sure our choices will find approval through the clinical pipeline as well as the regulatory pathway. And continuing to have that feedback loop is really helpful, ensuring that we don't go down the wrong path and spend months making what we think is a perfect product that doesn't fully address a clinical need or has the wrong form or function."

Another of Marks' favorite aspects of the fellowship thus far is an entrepreneurial series which Dr. Apiou has created, bringing together successful innovators, MDs and PhDs, from Massachusetts General Hospital every couple of months to share their translational know-how and expertise. "One of the common themes I noticed was how important it is to connect all aspects of laboratory work to the underlying clinical needs and questions. What exactly does a piece of data mean physiologically? How does data predict outcomes from treatment? If you've created a tool that can measure something better than existing devices, how does this improvement effect a doctor's daily routine? How does it impact their diagnoses, and ultimately patient outcomes? That's where this translational bridge lies," Marks continues: "It is understanding - at the start - how your experiments and your data fundamentally connect to clinical problems. That's been a really insightful aspect to the work I'm getting to do here."

That aspect is among her advice for future applicants for the fellowship: "Make sure your proposal is not just focused on the minutia of the science. While I was putting together drafts and going over them with Drs. Evans and Apiou, I had a tendency to get really deep into the details of 'this is the exact experiment that I want to do.' It's important to take a step back and look at the big picture and emphasize the translational component: how is what you are doing motivated by needs in clinical care? Successful translation is not just having doctors like an idea; there's also the business and regulatory aspects of a successful program. I've learned a ton about the types of communication needed when discussing my work in business vs clinical vs scientific settings."

Winning the fellowship was also a kind of affirmation for Marks, as it pertains to her involvement with SPIE. As a PhD candidate at Texas A&M, she was the SPIE chapter president. Actually, she notes, she's had almost every SPIE chapter role at some point: "I was the secretary and the treasurer then the VP then the president, so I was really involved in SPIE and have always loved the organization. We did a lot of K-12 outreach, and I learned most of the optics I know from trying to answer the questions of young kids and their parents, and trying to format new demos every year to keep things interesting. That side of SPIE, the K-12 outreach, is this whole other side of SPIE that I think people don't see often enough. I've always loved the SPIE's mission to make photonics a less scary word and to keep kids excited about light and light-based sciences."

Or even, it seems, keeping post-graduate researchers excited about - and engaged with - the life-healing properties of light.

All photos are courtesy of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine

Learn more about the SPIE-Franz Hillenkamp Fellowship in Problem Driven Biophotonics and Biomedical Optics. Applications for the 2019 fellowship are due 7 September 2018.

Comments

Post a Comment